Communication is a joint activity

Our previous article analyzed the fantastic benefits of reading aloud to improve your speaking in second languages. However, the optimal version of this exercise should involve:

- one reader and an audience

- several readers without an audience

- or several readers with an audience.

Each of these scenarios elevates the experience in multiple senses.

The neuroscientist Dr. Lisa Feldman Barrett reminds us that we always regulate each other’s nervous systems, whether consciously or not. Communication is a joint activity in which the speaker and listener’s brain activities couple when successful, and uncouple when it fails. When communication is successful, we are synchronized; when unsuccessful, we are desynchronized. Considering that having engaging conversations, small or big, is the primary motivation for learning a second language, exploring the effects synchronizing with and desynchronizing from others have on us emerges as fundamental for second language speakers.

We may also see this way: As we strive to improve our fluency, we endeavour to desynchronize from our current non-fluent selves and synchronize with the future fluent individuals we aspire to become. How can we synchronize with our future selves? By synchronizing with other fluent speakers who are already there.

And shared reading aloud appears to be one of the best practices for exercising both kinds of synchronization!

Improve your Speaking with Shared Reading Aloud: 8 Benefits

Let’s now explore what researchers in the fields of Neuroscience and Cognitive Science have discovered about shared reading aloud:

- It boosts empathy and emotional awareness

On the one hand, when we read aloud with someone else, we engage with the emotions and feelings conveyed by the texts themselves. On the other hand, we interpret the intentions and meaning our partner readers impart through the words. Moreover, there’s another layer: we receive cues about the person behind the reader and their emotional state at the moment of reading. We also glean hints about our feelings from how we read and how others react to our way of reading.

This helps us discern when the reader, or ourselves, might be lost; when we are “in the flow” and enjoying ourselves; or when adjustments such as slowing down or speeding are needed. This three-dimensional awareness is critical for navigating real-life conversations in a second language.

- It serves as a mirror

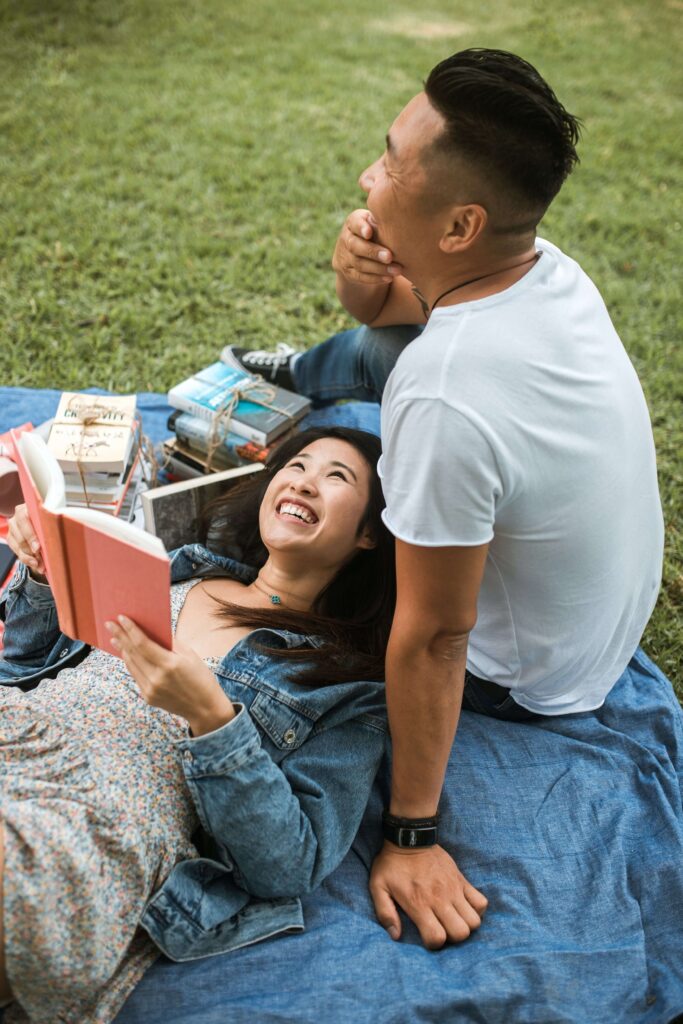

When we read with a teacher or other proficient speakers:

Teachers and proficient speakers act as a mirror and reflect what we should try to emulate: we detect what sounds good in them and what doesn’t quite yet in ourselves. Similarly, we identify what sounds good in ourselves and should be retained.

It provides additional support to the learners, as we can pause to ask questions and seek clarifications. We can also revise and repeat passages to strive for synchronization with the ideal version.

When we read with other speakers of the same level:

We serve as mirrors to each other, mutually learning from one another. We observe what sounds good in others and may wish to imitate it. Conversely, we notice what doesn’t sound right in others, prompting us to strive for self-improvement. And vice versa.

- It engages our minds in joint, deep, sustained attention

When you read a written text aloud with another person or a group, you feel “compelled” to keep up with the others and expect the same from them. Your reading team might have chosen to read a text from start to finish or agreed on a time frame to read as much as the time allows. The text, the time, or both serve as your common goals, providing a shared purpose.

During the reading, you enter a state of mind akin to that of artists when they say: The show must go on! That state of mind means joint, deep, sustained attention for as long as the show goes. The reading, in this case, becomes the sole focus in the world at that moment. Shared read-aloud encourages the development of a sense of responsibility towards the group and prevents distractions from interrupting the present moment.

Studies have shown that individuals being exposed to a shared stimulus, and sharing a similar focus of attention and perception for some time develop emotional synchrony, which is our next point.

- It enhances (motor & emotional) Synchronicity through Neural Coupling

When people read aloud together they synchronize with each other. We synchronize with our partners regarding tone, speed, pitch, or emotional charge. Furthermore, the reading practice becomes a form of collective creation. Sometimes, synchronizing means aligning with what our partners are doing while others, it may mean deviating from their actions to add colour, a change, or an element of surprise for the benefit of the collective creation; our shared purpose.

Studies have shown that shared reading aloud synchronizes the brain activity of reader and listener in what is termed neural coupling in Neuroscience.

Recalling the words of Dr. Lisa Feldman Barrett:

When our social interactions go well, we experience emotional resonance by synchronizing our breath, movements, or heart rate. During this process, we undergo a ‘bath of chemicals’ (Gurdon) and become ‘chemically nurtured’. However, when synchronization fails, we are ‘taxed’; our chemicals become unbalanced, and we feel worse than before the interaction.

- Context and shared meaning enhance the retention of novel words

Neural synchrony is based not only on exposure to the same stimulus (sounds, words) but also on sharing an understanding of meaning (story). Achieving this requires joint engagement with semantic or narrative content.

These high-level brain processes synchronize between speaker and listener during natural speech. The stronger the neural coupling between speaker and listener during real-life conversation, the better the understanding. Shared reading aloud has shown to activate the same brain areas involved in processing narrative content in both speaker and listener. It has also been discovered that when synchronization during shared reading aloud occurs, it enhances the learning of novel words through the overall comprehension of the story. The mix of context, shared meaning, and joint engagement stimulates the retention of novel words.

- Anticipation enhances comprehension and communication

Studies have shown that during natural conversation, we engage in specific dynamics of neural coupling through anticipation and synchrony. On some levels, the speaker anticipates the listener for successful communication. On other levels, the listener anticipates the upcoming words to enhance comprehension. Yet, on others, they both synchronize simultaneously. Studies indicate that the better anticipation on the part of the listener, the better the understanding and communication.

Action (speaking) and perception (understanding and processing of meaning) are inextricably linked in communication. If successful communication is based on our prediction skills as listeners, reading aloud couldn’t be a better exercise to train that skill.

If, in addition, we use specific acting techniques to exercise anticipation, the better.

- It enhances understanding of the pragmatics of communication

The three-dimensional awareness enhanced by the experience of shared reading aloud is a fantastic tool for comprehending the pragmatics of communication, which is fundamental for second-language speakers.

In real-life situations, we should be aware that the cause of poor communication might be, at times, the absence of the right words. Yet, other times, semantics are not the cause of miscommunication, but rather flaws in turn-taking coordination, our mood or that of others, or external interference that disrupt the connection.

Mastering this “split awareness” is essential for understanding and mastering the pragmatics of communication in a second language. A general tendency among non-fluent speakers is to hold onto negative emotions when miscommunication occurs: embarrassment, guilt, and judgment.

Being able to infer our interlocutor’s intentions may be crucial for successful communication and healthy further learning. For this inference to work, we must exercise “split awareness” to better discern the potential causes of the misunderstanding.

Conclusion:

Reading aloud is one of these exercises that naturally encourages us to synchronize with another human being. Additionally, we synchronize with other fluent voices’ ways of speaking and thinking (narrator, character). This exercise also enhances split awareness and listening, which are key for communication.

Our Tip:

Pick up a book you love.

Find its translated version in your target language.

Find a ‘partner in crime’.

And exercise shared reading aloud.

Synchronization will take care of the rest for you (as long as you keep showing up at the readings)!

Resources

Bourguignon, Mathieu, et al. “Neocortical Activity Tracks the Hierarchical Linguistic Structures of Self-Produced Speech during Reading Aloud.” NeuroImage, vol. 216, no. 116788, 2020, p. 116788, doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116788.

Gurdon, Meghan Cox. The Enchanted Hour the Enchanted Hour: The Miraculous Power of Reading Aloud in the Age of Distraction. HarperCollins, 2019

Lane, Holly B., and Tyran L. Wright. “Maximizing the Effectiveness of Reading Aloud.” The Reading Teacher, vol. 60, no. 7, 2007, pp. 668–675, doi:10.1598/rt.60.7.7

Piazza, Elise A., et al. “Neural Synchrony Predicts Children’s Learning of Novel Words.” bioRxiv, 2020, doi:10.1101/2020.07.28.216663.

Roberts, Richard M., and Roger J. Kreuz. Becoming Fluent: How Cognitive Science Can Help Adults Learn a Foreign Language. MIT Press, 2016

Silbert, Lauren J., et al. “Coupled Neural Systems Underlie the Production and Comprehension of Naturalistic Narrative Speech.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 111, no. 43, 2014, doi:10.1073/pnas.1323812111.

Stephens, Greg J., et al. “Speaker–Listener Neural Coupling Underlies Successful Communication.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 107, no. 32, 2010, pp. 14425–14430, doi:10.1073/pnas.1008662107.

Ulanoff, Sharon H., and Sandra L. Pucci. “Learning Words from Books: The Effects of Read-Aloud on Second Language Vocabulary Acquisition.” Bilingual Research Journal, vol. 23, no. 4, 1999, pp. 409–422, doi:10.1080/15235882.1999.10162743

Wolsey, Thomas Devere, and Diane Lapp. “Teaching/Developing Vocabulary Using Think‐aloud and Read‐aloud Strategies.” The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching, Wiley, 18 Jan. 2018, pp. 1–9, doi:10.1002/9781118784235.eelt0747

*

Podcast: Huberman Lab

Huberman, Andrew. “Dr. Eddie Chang: The Science of Learning & Speaking Languages.” Huberman Lab, Huberman Lab, 23 Oct. 2022, https://www.hubermanlab.com/episode/dr-eddie-chang-the-science-of-learning-and-speaking-languages

Huberman, Andrew. “Dr. Erich Jarvis: The Neuroscience of Speech, Language & Music.” Huberman Lab Podcast, episode 87, 28 Aug. 2022, https://www.hubermanlab.com/episode/dr-erich-jarvis-the-neuroscience-of-speech-language-and-music

Huberman, Andrew. “Dr. Lisa Feldman Barrett: How to Understand Emotions.” Huberman Lab Podcast, [episode number not available], 24 Oct. 2023, https://www.hubermanlab.com/episode/dr-lisa-feldman-barrett-how-to-understand-emotions